Development update

Interview: Dr Muhammad Musa

April 9, 2019Development update

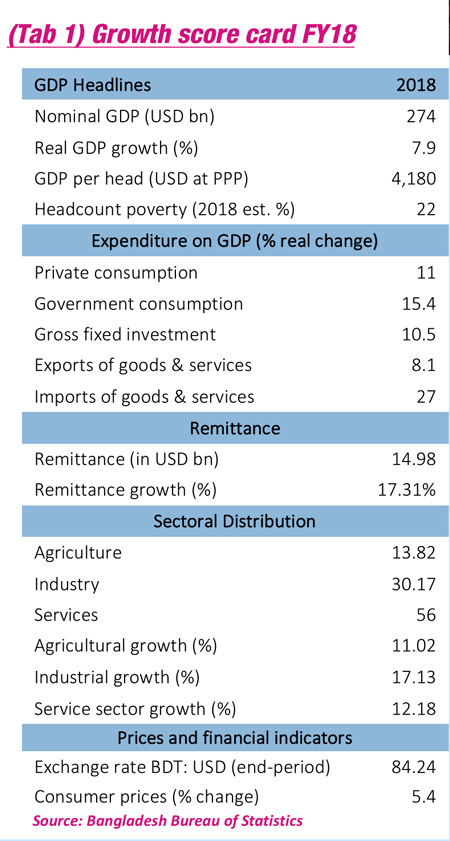

Bangladesh has achieved the highest-ever 7.86 per cent gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate during the 2017-18 fiscal year (FY18). This has surpassed the interim estimate of 7.65 per cent. During this period, the size of GDP grew to USD 274.11 billion from USD 240.72 billion and the per capita income increased to USD 1,751 from USD 1,610 in the previous fiscal year,posting a 6.61 per cent growth1. The BBS also estimated that the contributions of agriculture, industry, and service sector were 13.82 per cent, 30.17 and 56 per cent respectively. Based on trend data from the House Hold Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) of 2015, it is estimated that as of 2018, the poverty rate stands at 21.8 per cent and the extreme poverty rate at 11.3 per cent, down from 23.1 per cent and 12.1 per cent respectively in 2017.

Bangladesh has achieved the highest-ever 7.86 per cent gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate during the 2017-18 fiscal year (FY18). This has surpassed the interim estimate of 7.65 per cent. During this period, the size of GDP grew to USD 274.11 billion from USD 240.72 billion and the per capita income increased to USD 1,751 from USD 1,610 in the previous fiscal year,posting a 6.61 per cent growth1. The BBS also estimated that the contributions of agriculture, industry, and service sector were 13.82 per cent, 30.17 and 56 per cent respectively. Based on trend data from the House Hold Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) of 2015, it is estimated that as of 2018, the poverty rate stands at 21.8 per cent and the extreme poverty rate at 11.3 per cent, down from 23.1 per cent and 12.1 per cent respectively in 2017.

During the FY18, despite various ups and downs in the world market, Bangladesh’s export has inched up 5.81 per cent to USD 36.67 billion.

Inward remittances in FY18 bounced back after a falling trend in the previous fiscal. Bangladesh Bank reported that expatriates remitted USD 15.54 billion in 2018, a jump of 14.79 per cent over 2017 and slightly higher than the total figure of FY16. Notably, money sent by non-resident Bangladeshis makes up about 12 per cent of Bangladesh’s GDP and unlike other countries, has a strong poverty reduction impact in Bangladesh.

The overall reduction of income poverty has been very good. The acceleration of economic growth, growing remittance, expansion of social safety net and activities of a large number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) is said to have contributed to this progress2.

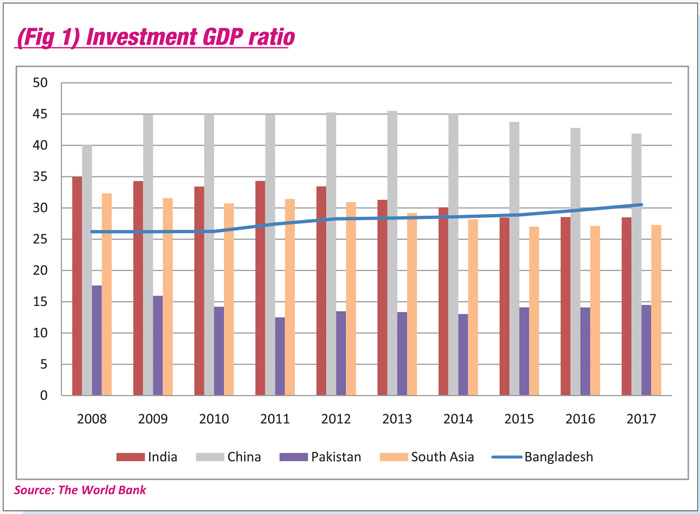

One clear evidence from the data for FY18 and a few preceding years is that Bangladesh’s growth is propelled by growing investment (see Fig 1). In FY18, Bangladesh invested 31.23 per cent of her GDP—which is higher from the FY17 figure of 30.51 per cent and the highest in Bangladesh’s history. The rate is, however, lower than the magic rate of 35 per cent, which the experts believe is required for double-digit growth.

To promote investment, Bangladesh follows a simple strategy – first invest in public sector, create the infrastructure and other factors needed to ultimately promote private sector investment.

In his 2018-19 budget speech, the honourable finance minister AMA Muhit clearly articulated this expectation and said that “the purpose of this investment is to create investment supporting environment for the private sector3.” However, despite growth in the public sector, the private investment seems to have stagnated (see Fig 2).

The answers to this mystery lie in both the realities of public investment and private investment contexts.

Public investment

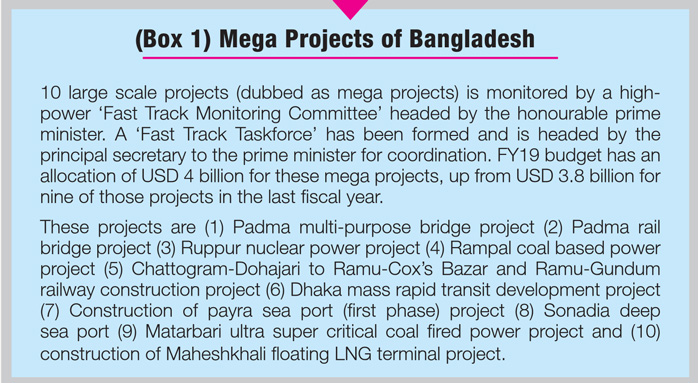

The large and complicated ‘megaprojects’, which constitute the majority of our public investment portfolio (see Box 1), needs a number of years to complete and start producing the impacts. Hence, it would be unwise to expect the ‘private investment’ boosting impact of public investment too soon.

Having said that, experts point out three key issues that need our attention.

First, the contribution of international implementing agencies in the development of local value chain is insignificant. Most white collar jobs and a good portion of blue collar jobs go to foreign workforce, as lack of skills and international certification stops local industries from working as sub-contractors. A wisely drawn plan to make Bangladeshi labour force and companies compatible with the standard is needed. Additionally, public support to the local sub-contractors is needed to ensure that these investments crowd-in more local investment and that technology is transferred. This can also ensure sustainable operation of these often turn-key projects by developing local capacity.

Second, issues of managing implementation by local public agencies often cause implementation delays. Save and except the ‘Dhaka Metro Rail’ project, all the other mega projects are behind schedule, sometimes by a few years.

Of the 10 mega projects currently under high-level supervision, five are currently in progress while four are yet to cross the starting line. The resulting delays are not only pushing the final price tag of the project up by a significant amount but also delaying their impact on boosting private investment.

Finally, the third issue is related to the ‘quality’ and discipline of disbursement. Only able to spend 60-65 per cent of the ‘Annual Development Plan’ is a problem of the past; last year the implementation rate was a record 93.7 per cent. Various financial reforms such as the procedures of the fund release as well as effective coordination by ‘Economic Relations Division’ have significantly improved disbursement rate. However, data from the Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED) of the Ministry of Planning suggested that around 41 per cent of the budget spending took place during the last two months of the

financial year 2018. While accounting procedure and reporting lag must have made the situation look worse than it actually was, the data clearly points out the procedural indiscipline. Such unplanned activities make it difficult for local firms to adequately compete with large international counterparts who might have sufficient access capacity to respond in short notice.

Private investment

Delayed impact of public investment alone cannot explain the stagnant growth of private investment – other bottlenecks are in play as well. Several global research publications such as the “Doing Business 2019”[1] , “The Global Competitiveness Index 2018 (GCI 2018)”[2] , “LDC report 2018”[3] , etc have shed light on some of these challenges.

[1]The World Bank Group, Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform, Washington, DC, USA, Oct. 2018,

[2] World Economic Forum, The Global Competitiveness Report, Cologny, Switzerland, Oct. 2018,

[3]United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, LDC Report 2018: Entrepreneurship for structural transformation: Beyond business as usual, Geneva, Switzerland, Nov. 2018

Administrative and legal procedures

Archaic, complicated, expensive, and time consuming administrative and legal procedures might be the most major impediments for private investment in Bangladesh.

Archaic, complicated, expensive, and time consuming administrative and legal procedures might be the most major impediments for private investment in Bangladesh.

The ‘Doing Business 2019’ report points out that even the simple procedure of registering a business takes 19 days in Dhaka compared to a day in New Zealand. Similarly, it takes 148 days to get an electricity connection in Dhaka, which takes a fraction of time in most other countries. Unsurprisingly, hence, 2019 Doing Business Index (DBI) ranked Bangladesh lowest among all countries of the South Asia region at 176th place among 190 countries. Notably, this position is significantly lower from Bangladesh’s 130th position in the first DBI of 2014.

Bangladesh’s legal system, which is already clogged with a massive 3.3 million pending cases7, is an impediment too.

It is complicated and time- consuming to enforce the contract, or ensuring property rights, or even dealing with insolvency in Bangladesh. Although the CGI 2018 showed that Bangladesh is ahead in terms of ICT Adoption and health indicators of the South Asian average, in most cases we are behind. Especially, the GCI 2018 ranked the country’s land administration system as one of the worst in the world (135th among 140 countries). These bottlenecks discourage investments into Bangladesh market and indirectly reduce the country’s competitiveness (see Fig 3).

The Governance Innovation Unit (GIU) at the Prime Minister’s Office which has a mission to “.. .ensure that the public sector is putting citizens first by implementing good governance reforms and innovations that meets or exceeds citizen expectations” is perfectly positioned to take the lead to improve both business environment as well as competitiveness. Specific initiative in partnership with the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA) and in association with business chambers can bring early results.

Structural weaknesses

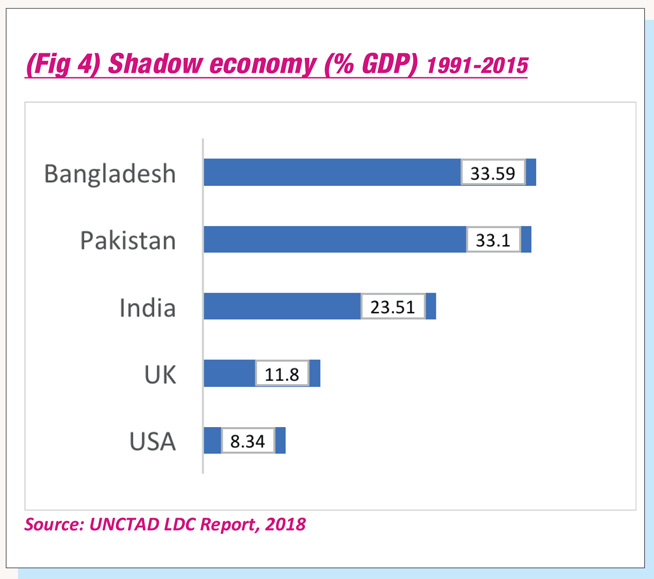

A United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) study shows that the current economic structure of Bangladesh’s private sector is not ready for take-off. While the nation is still dependent on agriculture, the industry and services sectors seem to be trapped in the cycle of low-cost, low-value, small size enterprises.

The non-agricultural sector is characterised by self-employment, who are self- employed by necessity. Enterprises in the non-agricultural sector are small and have very low capacity to absorb risk. As such, most remain in the informal sector or being in the ‘shadow’, as the LDC report has termed them (see Fig 4). UNCTAD has estimated that the size of the ‘shadow’ economy of Bangladesh is about one- third of the official GDP. The challenge is that these participants of the shadow economy do not have access to business services such as access to formal credit and ensure formal employment and hence do not contribute in capital formation and thus promote new entrepreneurs.

In this context, property monitored entrepreneurship development programme for the educated youth might be a policy direction to adopt. Improving the efficacy of G2B services especially by promoting venture capital and adopting supportive policy framework for angel investors can be helpful.

Financial market

Accessing finance is an overwhelming challenge in Bangladesh. Besides internal ‘crises’ that has effectively limited bank and non-bank financial institutions’ capacities to contribute, low level of ‘financial inclusion’ has also left a large proportion of people outside the reach of financial services.

Accessing finance is an overwhelming challenge in Bangladesh. Besides internal ‘crises’ that has effectively limited bank and non-bank financial institutions’ capacities to contribute, low level of ‘financial inclusion’ has also left a large proportion of people outside the reach of financial services.

The growing number of non-performing loans (NPLs).which reached nearly BDT 1.0 trillion in September 2018, is probably the best indicator of the ‘crises’ in the banking sector . During the first nine banks, the eight state-owned banks represented nearly 50 per cent of the NPLs as of June 2018. The situation not only depleted the capital of the banks but also forced them to set aside otherwise loanable resources as reserves. Consequently, private credit growth has reached the months of the calendar year, the growth of NPL was 34 per cent. Of the 57 scheduled banks, the eight state-owned banks represented nearly 50 per cent of the NPLs as of June 2018. The situation not only depleted the capital of the banks but also forced them to set aside otherwise loanable resources as reserves. Consequently, private credit growth has reached the lowest in 22 months and is expected to remain low in the coming days (see Fig 5).

The ‘financial inclusion’ problem has several faces but the result is the same: a large segment of private enterprises is deprived of formal financial services. Having less than nine branches per 100,000 people of Bangladesh, most of which are concentrated in the major towns, a large segment of rural Bangladesh simply do not have banks. Of course, there are a large number of microfinance providers active in these areas. But, except for a notable few, the MFIs remained fixated with personal credit and seldom have products suitable for micro-enterprises.

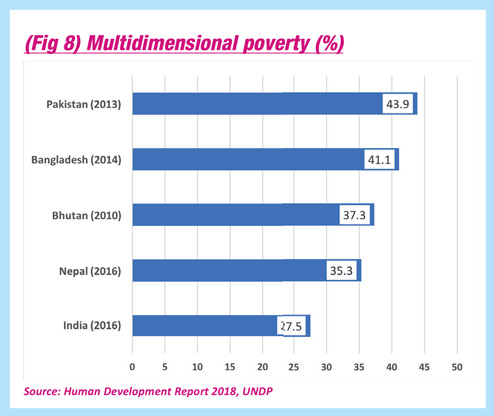

However, not having appropriate products is not only a rural problem. The second largest sector after RMG in terms of transaction is the micro-enterprise sector. Bangladesh has over 1.3 million micro-entrepreneurs who are transacting USD 18.4 billion annually. Every year, about 50,000 new micro-enterprises are opening their doors. UNCDF estimates that these entrepreneurs need between USD 3.66 to USD 5.29 billion annually. But they only have access to around USD 778 million from both banks and microfinance institutions . It seems that our banking sector is not interested to tap the large potential market (see Box 2) for an interesting perspective.

Preparing for the big leap

Bangladesh is poised to make a big leap in terms of economic growth. Be it the Forbes 2014 article that described Bangladesh as a capitalist haven[1] or the recent report by HSBC that says Bangladesh is becoming the 26th largest economy in the world from the current 42nd[2] position, there is a growing consensus about Bangladesh’s future. Similarly, the December update from the Economist Intelligence Unit predicted that the “real GDP growth will average 7.7 per cent per year in 2018/19-2022/23,

bolstered by sustained gains in private consumption and investment. Private consumption will be supported by rising personal incomes.”

Joining the bandwagon, the December report by several UN agencies concludes that “the Bangladesh economy is set to continue expanding at a rapid pace, underpinned by strong domestic demand, especially large infrastructure projects and new initiatives in the energy sector[3]. ”

There appears to be a consensus among the commentator of the necessary conditions to attain such an impressive feat as well. First of all, according to them, it is all dependent on ongoing political stability. In addition, most agreed that Bangladesh will have to put special emphasis on four key areas like economic diversification, reducing inequality, supporting long-term investment and tackling institutional deficiencies.

[1] Forbes, Alyssa Ayres, Bangladesh: Capitalist Haven, Oct 28, 2014

[2] Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC), The World in 2030: Our long term projections for 75 countries, 2018

[3] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN/DESA), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the five United Nations regional commissions (Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), Economic Commission for Europe (ECE), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) and Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA)), World Economic Situation and Prospects 2018, December2018, NY, USA

Transforming growth into progress

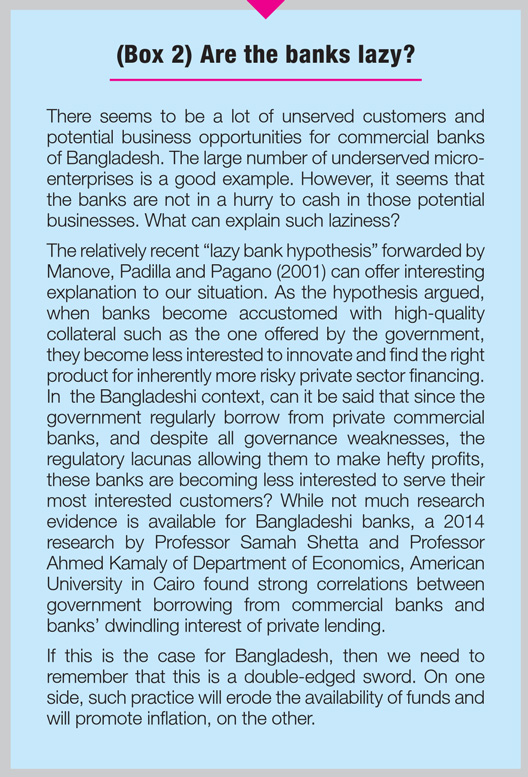

As the Constitution of Bangladesh professes, growth is only as useful as its impact on the lives of men and women[1]. In that context, when measured in terms of the Human Development Index[2], Bangladesh’s progress has been enviable (see Fig 6). The 2018 HDI placed Bangladesh at 136th among 189 countries and territories[3]. With an HDI scone of 0.608, Bangladesh has moved up three places, compared to its 2015 standing by improving all three components of the index. However, a detailed read of this report along with several other recent studies do raise some concerns about Bangladesh’s quality of development.

[1]Article 10 of the Constitution of People Republic of Bangladesh on the fundamental principles of the state reads “10. A socialist economic system shall be established with a view to ensuring the attainment of a just and egalitarian society, free from the exploitation of man by man.

uThe ‘Human Development Index’ (HDI) measures long-term development progress in terms of long healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. The index is the most recognized measure of people’s wellbeing.

[3]United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2018, NY, USA. September 2018

Quality concerns

Some quality aspects of Bangladesh’s development journey need closer review. While a baby born in Bangladesh is expected to live for 72.8 years (a South Asia champion), s/he is expected to only have around 60 years of healthy life. With only 4.7 physicians and six hospital beds

for 10,000 people, Bangladesh simply cannot do any more for this newborn.

Similarly, the standard of living of the average citizen of Bangladesh could have been better in comparison to the per capita income. Around 58 per cent Bangladeshis are involved in vulnerable jobs.Only about 69 per cent of the rural population have access to electricity, and around 47 per cent Bangladeshis

use improved sanitation. All of these indicators, according to the HDR, puts Bangladesh among the bottom third of the countries. The only saving grace in this regard is that 97.3 per cent Bangladeshis have access to safe drinking water.

The biggest quality-related concern is quality of education. This issue will be discussed in further detail in a section below.

Inequality

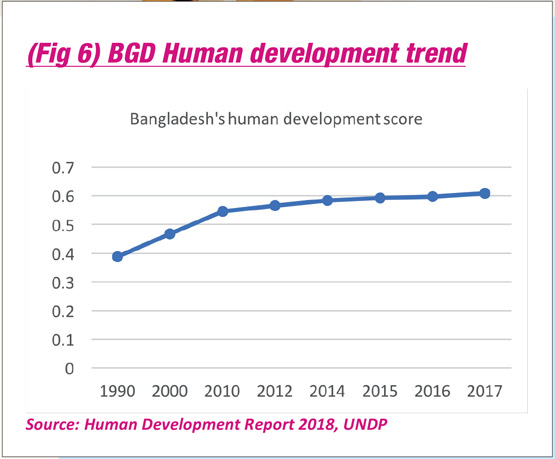

Despite accelerated GDP growth rate, the rate of poverty reduction is slowing down. It averaged 1.8 per cent per year between 2000 and 2005, 1.7 per cent per year between 2005 and 2010; but declined to 1.4 per cent per year between 2010 and 2017 (see Fig 7) for regional comparison).The residual poverty that the country is dealing with is complex and entrenched in nature, which explains this slowdown, but inequality, both income and non-income, is responsible too.

On the income side of inequality measured with the Gini coefficient, Bangladesh seems to have been regressing. The 2015 Household Income and Expenditure Survey by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) estimated the income Gini coefficient of Bangladesh at 0.483 nationally, which was 0.498 in rural areas and 0.454 in urban areas. According to the report, the poorest 5 per cent Bangladeshi only receive 0.23 per cent of overall income, which was 0.78 per cent in 2010. At the same time, the income of the richest 5 per cent has grown from 24.61 per cent to 27.89 per cent. But the worst assessment in this regard was recently made by Dr Debapriya Bhattacharya (see Tab 2). He has shown that when calculated on wealth, the Gini coefficient was as high as 0.74 in 2010.

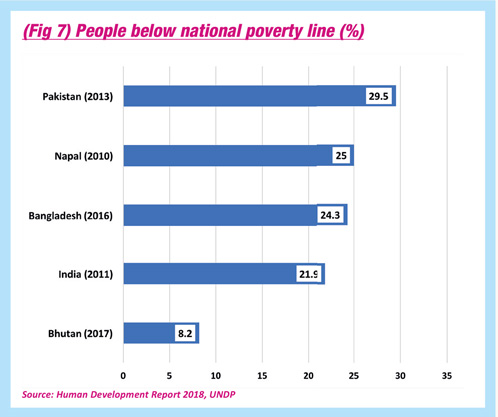

The income inequality is often associated with nonincome inequality, but more often the non-income inequality is created by non-financial factors such as social structure, cultural norms, etc. The exact measure of inequality caused by such diverse reason is difficult. The Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) and UNDP are popularising the concept of multidimensional poverty to measure deprivation in all the dimensions of human development (health, education and living standards). In terms of MPI, the UNDP reported in 2018 that more than 41 per cent people live in multidimensional poverty in Bangladesh (see Fig 8).

In addition to MPI, the Human Development Report also measures what is known as inequality-adjusted HDI to measure welfare loss due to inequality. Going beyond the average achievements, the IHDI reveal large inequalities across human development dimensions which can make sustainable progress difficult. According to this year’s HDI update, Bangladesh stands to lose 24 per cent of human development due to inequality.

What is Bangladesh doing to address the growing inequality?

Oxfam and Development Finance International (DFI) attempted to measure each of the countries commitment to end inequality through what they call ‘Commitment to Reducing Inequality’ (CRI) Index16. This year’s CRI placed Bangladesh at 148th rank out of the studied 157 countries – clearly indicating lacunas in our policies and actions. The report highlighted various legal issues and practices such as less regressive tax system, more reliance on indirect taxation such as VAT, lax labour laws, etc as potential loopholes for Bangladesh that may encourage inequality.

Gender divide

Gender-based inequality is not just another form of inequality but probably the most pervading and damning one. Bangladesh is generally regarded as a good performer in her class globally. In this year’s Human Development Report two separate set of indicators were used to measure the divide. The life-course gender gap attempted to measure the disparity in “choices and opportunities over the life course – childhood and youth, adulthood and older age. The indicators refer to health, education, labour market and work, seats in parliament, time use and social protection ”. Of the nine indicators for which Bangladesh data was available, other than ‘sex ratio at birth’ indicator, Bangladesh has done poorly (in five indicators) or average (in three indicators).

The other set, dubbed as “Women Empowerment” panel, contains a selection of women-specific indicators to measure three dimensions of empowerment in reproductive health and family planning, violence against girls and women and socioeconomic empowerment. Once again, out of the 13 empowerment indicators, Bangladesh has shown quality performance in three categories (contraceptive prevalence, unmet need for family planning, mandatory paid maternity leave) and performed poorly in eight other categories. However, information on two indicators remain missing.

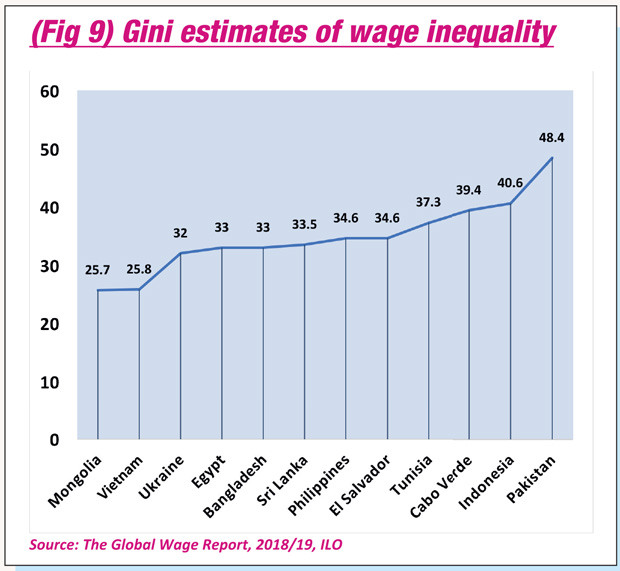

Amidst these conerns all the above worries, there is at least one good news for Bangladesh’s performance in reducing the wage gap between men and women. The Global Wage Report (GWR) of ILO analyses gender pay gap worldwide using the Gini coefficient. According to the report, Bangladesh’s wage gap Gini coefficient is 33 (see Fig 9). Bangladesh’s score suggests that wage inequality in the country is one of the lowest in South Asia. The data for gender pay gaps using hourly wages in Bangladesh shows that the mean gap is -5.5 per cent and the median +0.3. This means that on average, women earn 5.5 per cent more than men. However, when gender pay gap is evaluated based on monthly earnings, both the mean (+7.2%) and median (+4.7%) notes that women on average, earn less than men in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh, a lower-middle income country, is the only country whose factor-weighted mean hourly wage gender pay gap is positive. It can be inferred from the data, thus, in part- time jobs or hourly based payment, employers prefer to recruit women due to the nature of the job and offer better wages. On the other hand, in monthly wage or permanent jobs, men are given priority over women and therefore, the gender wage gap is higher compared to monthly wage payment.

Similar findings were reflected in another global report this year published in December . According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2018, Bangladesh has held its top-most position among the countries of South Asia in ensuring gender equality for the fourth time in a row. According to the Global Gender Gap Index, Bangladesh has slipped one rung to the 48th position among 149 countries in the world, but still ahead of all other countries in the continent except the Philippines, according to the report.

Sustainability

One of the major lacunae of Bangladesh’s MDG performance was environmental sustainability. The biggest concern was forest cover, in which Bangladesh struggled. The HDR this year also attempted to identify strengths and weaknesses with respect to environmental sustainability. Bangladesh fared well with regard to carbon emission and consumption of fresh water with respect to the reserve. Bangladesh’s valiant attempt to introduce solar home system brought Bangladesh’s performance with regard to energy mix to the average level. However, the country is still struggling to maintain forest cover. In fact, the actual cover has declined 4.4 per cent from 1990 to 2015. Additionally, mortality due to environmental degradation caused by air pollution, water quality, etc is identified as a challenge for Bangladesh.

On the socioeconomic sustainability indicator sets, Bangladesh’s performance is as good as saving practices, growing capital formation rates and low debt services positively influenced Bangladesh’s economic sustainability. However, the low skillset of labour, the concentration of export in only RMG and low of budget allocation in health and education challenges Bangladesh’s social sustainability.

Harnessing the demographic dividend

Bangladesh will continue to have an overwhelmingly young population for at least two more decades, if not more. During this time a smaller proportion of the population will be dependent (age 14 and younger, and 65 and older) on the larger number of working population (age 15-64). Hence, there will be higher national saving, greater private investment, higher number of innovation, and the list goes on. This demographic condition is known as the demographic dividend. Two additional details are important to note. First, demographic dividend is also associated with heightened socioeconomic pressures, particularly the need to generate jobs for those entering the labour market.

Second, the demographic dividend is time bound. With time, the dividend goes away. It is estimated that as of 2017, more than 65 per cent of Bangladeshis are of working age (15 to 64 years). However, we have already seen a sharp fall in fertility rates, from 6.6 children per woman in 1980 to 2.5 in 2010. The rate is expected to go down further in the next decade. It is expected that the working-age population in Bangladesh will expand by an annual average of just 1.5 per cent in 2019-30.

What demographic dividend guarantees are that there will be ample supply of human resources? However, whether the available resources are capable to contribute and whether there is enough scope for these young people to contribute determines how well a nation can translate the demographic dividend into the economic dividend.

Do our youth have the right skill set?

Several recent reports, studies and discussions have highlighted poor teaching standards, low teacher attendance and relatively high student-teacher ratios as reasons behind the low skill set of Bangladeshi workforce. The high number of school going population and low tax base make it difficult for administrators to allocate sufficiently for schools. Quality of infrastructure in rural areas, where most students reside, also make it difficult to address specific needs of rural communities within a centralised system like the one that we have.

This year’s Human Development Report identified the high teacher- student ratio at the primary level, quality and proportion of primary teachers who are trained, students’ access to the internet as problematic for Bangladesh. When read alongside the Global Competitiveness Index 2018 and the Doing Business 2019 report, a much grimmer picture of education quality, especially at the tertiary and vocational level, emerges.

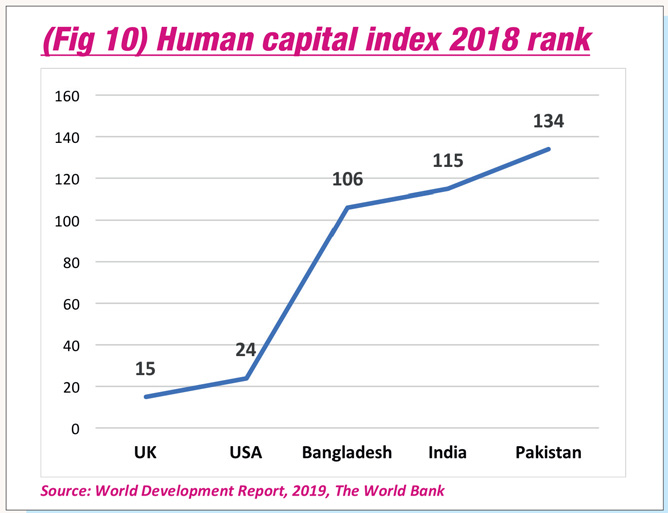

The World Development Report (WDR) 2019 concluded that Bangladesh’s Human Capital position is 106 among 157 countries (see Fig10). In comparison to the neighbouring countries of South Asia, Bangladesh’s position is better. However, for a country that does not have a huge amount of mineral resources or other physical resources to lean back on, and the demographic dividend is what the nation is aiming to harness, the ranking of 106 is not much to celebrate. WDR concludes that Bangladesh’s pre-primary, primary, and secondary education system perform poorly in inculcating the basic skills and learning ability. According to the World Bank, children in Bangladesh can expect to complete 11 years of pre¬primary, primary and secondary school by age 18 but once adjusted for quality, that 11 years of learning only reaches equivalence of 6.5 years.

In this context, Bangladesh may look towards innovative teaching¬learning models to address the acute infrastructure inadequacy and lack of trained teachers using technology and leveraging such ideas as self-organised learning. Investing in technical and vocational training for those who have already completed secondary schools might be a prudent strategy too.

Are we creating the right scope?

The aspect of transforming demographic dividend into economic dividend has to do with the right opportunities for this large number of young people who are entering the job market. However, Bangladesh’s ability to absorb these new entrants are waning fast. The Labour Force Survey by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics reveals that on an average, between 2003 and 2016, the Bangladesh economy generated more than 1.15 million jobs per year; but this pace is falling. Between 2003 and 2010, the total employment grew by 3.1 per cent a year. This rate dropped to 1.8 per cent per year from 2011 till 2016. Another big problem is the unequal distribution of jobs among different parts of the country. Dhaka division alone accounts for 45 per cent of all industry jobs and 37 per cent of all services jobs of the country. Also, the Labour Force Survey of different years shows that the unemployment problem is more acute among highly educated youth!

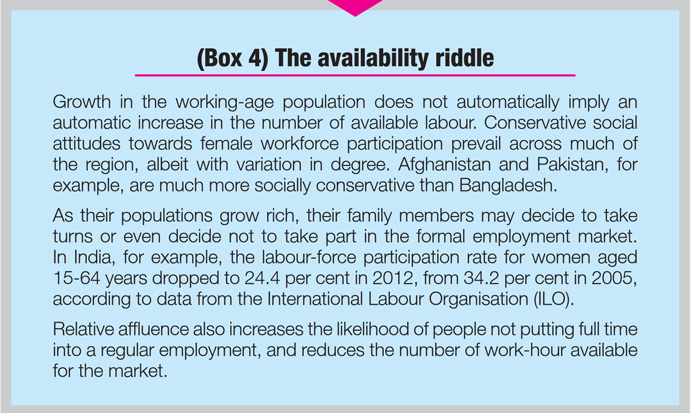

So what options are open for Bangladesh to ensure that the 2.1 million new entrants will get the scope to work (see Box 4). Throughout the economic history, the most common option is the industrial sector as the chosen sector for employing the youth. Bangladesh has a relatively underdeveloped manufacturing sector with little deposits of mineral resources and abandoned supply of low- cost hydroelectricity.

Of course, we have a world-class, large-scale export-oriented garment manufacturing sector, which has been the largest manufacturing sector. But the absorption capacity of the sector is waning. Automation and competition pressure is pushing the RMG units to become more capital intensive. The country is exploring a newer competitive niche in other manufacturing industries such as pharmaceutical and light engineering but none of these industries promise large scale employment.

Other countries, especially neighbouring India, have created employment for its growing youth segment in the services sector, more specifically in the technology-based outsourcing industry (see Fig 11). Not only is it a massive provider of employment, but the contribution of the sector in maintaining a healthy foreign currency reserve is also significant. Bangladesh has made some useful headways in this right direction.

Currently, Bangladesh contributes 15 per cent to the global labour pool online by means of its 650,000 freelance workers. However, the experience of most other Asian countries shows that since the service sector depends on both the local industrial and agricultural sector unless a country could connect itself to the global value chain, services sector on its own seldom creates employment. In other words, Bangladesh now needs to concentrate more on getting connected to the international value chain. Hence, proper international certification of our youth will be critical. This can ensure their participation in the online job market more effectively and contribute at a higher level.

The other traditional sector which is still the major employment provider in Bangladesh is the agricultural sector, though its importance is decreasing every year. Jobs left in the sector are mostly low- income and low-value-added, and hence are unattractive to the youth. Though commercial agriculture has shown some hope in south-east Bangladesh, the use of tools and the gradual decline of the cultivable land area is a limiting factor for the sector as a source of employment. Interestingly, the participation of women in agriculture is experiencing a marked rise in recent times.

Are we ready for 41R?

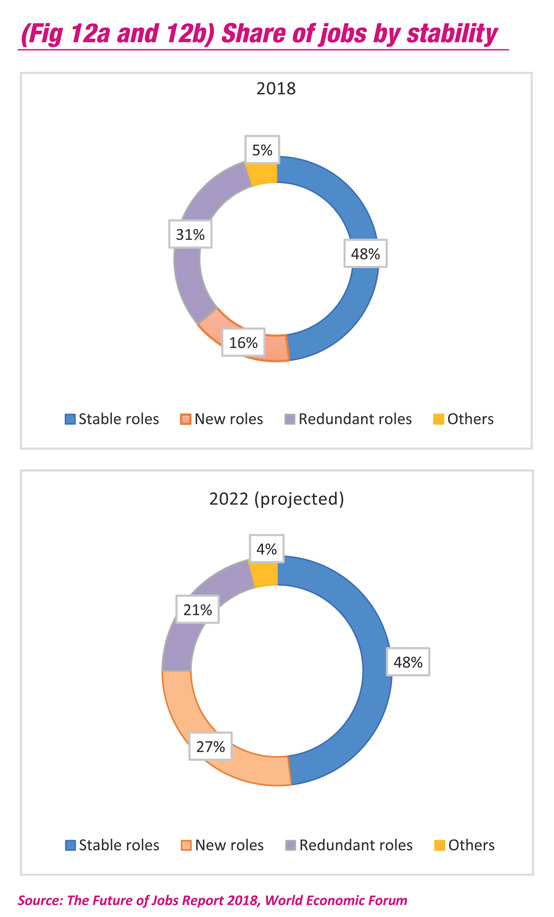

We are standing at the doorstep of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) as the traditional manufacturing processes are harnessing new technology, such as the Internet of Things (loT), and Artificial Intelligence (Al) and leveraging real¬time data. The initial discussion of how the 4IR is going to affect the labour force was akin to Karl Marx’s worries that “machinery does not just act as a superior competitor to the worker, always on the point of making him superfluous. It is the most powerful weapon for suppressing strikes.” In this context, the 2018 WDR basically debunked the fear (see Fig 12a and Fig 12b).

We are standing at the doorstep of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) as the traditional manufacturing processes are harnessing new technology, such as the Internet of Things (loT), and Artificial Intelligence (Al) and leveraging real¬time data. The initial discussion of how the 4IR is going to affect the labour force was akin to Karl Marx’s worries that “machinery does not just act as a superior competitor to the worker, always on the point of making him superfluous. It is the most powerful weapon for suppressing strikes.” In this context, the 2018 WDR basically debunked the fear (see Fig 12a and Fig 12b).

The report concluded that with the help of technology, work is constantly reshaped while the firms adopt newer ways of production, marketing, and sourcing their inputs. Overall, technology is creating newer jobs and newer sectors. Technology is also changing in a way that the workforce are acquiring skills that they need to make the best use of the employment opportunities offered by firms. Digital technology is also changing how people work and the terms on which they work. Hence, 4IR should have an overall positive impact on human beings and their living standards. The report projected that about half of today’s core jobs – making up the bulk of employment across industries – will remain somewhat stable in the period leading up to 2022.

But it is women who is likely to be most affected by automation because they tend to be employed in more routine tasks than men across all sectors and occupations. Routine tasks are more prone to automation. New IMF research estimated that 26 million women’s jobs in 30 countries, which is around 180 million jobs globally, are at risk of being displaced by technology in the next couple of decades.

However, there is no reason to assume that the transformation to industry 4.0 is automatic and without pain. Depending on how well each individual, community, country and region prepare and learn new ways of operation, there will be winners and losers. This year’s Global Competitiveness Index, which focused on different countries ability to be competitive in the 4IR era, poorly rates Bangladesh’s preparation. This new methodology, made up of 98 variables organised into twelve pillars, emphasised the role of human capital, innovation, resilience and agility as drivers of economic success in the 4IR era. Sadly but unsurprisingly, the GCI 2018 ranked Bangladesh at 103 — down from last year’s 102 — out of 140 countries. Compared to last year, Bangladesh’s ranking fell nine out of 12 pillars with lowest in business dynamism and product market. It may be interesting to note that, this year, neighbouring India climbed five rungs to 62. The Global Innovation Index, published in July this year, ranked Bangladesh 124 among 126 countries in terms of Human Capital and Research while the overall ranking was a low 116.

Hence, it is critical for Bangladesh to assess the factors which need to change in order to improve the quality and quantity of Bangladeshi innovation as well as the quality of tertiary education including in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). The copyright and patent related awareness need to be created and related public services need to be streamlined.

Focusing on job seekers

One particular development in Bangladesh has the potential to change the current situation dramatically. Bangladesh is aiming to establish as many as 100 special economic zones to attract both local but mostly foreign capital. Once operational, these zones will create a massive number of employment. Here again, it is important to forecast the skills needed in these new industries and to ensure that the Bangladeshi job seekers are equipped with the required skills and certifications to take advantage of those vacancies. Similarly, a quick stock of the mega projects and their employment needs can be used for targeted development of human resources to ensure that such opportunities are available for local unemployed youth.

The Bangladesh Awami League, the party that secured a landslide victory in the 11th Parliamentary Poll held on 30 December, has also promised to create 15 million more jobs during the next five years for 11.09 million more people who are likely to join the workforce during that period. The manifesto also promised a significant increase in investment in vocational and technical education and progress in the information and communication technology sector to build a workforce that can face the challenges of the modern world.

Looking forward

Most economic estimates suggest that the strong economic growth of Bangladesh in FY18 is going to sustain over the near future. Such prediction is remarkable because the formal economy slowed down in December and will take probably a couple of months in 2019 to get back to normal. However, the informal economy, especially in rural Bangladesh, is expected to experience the opposite at the same time. Last year, as many as 1,841 candidates ran their campaigns. Even if the political parties had spent 2.5 million for each campaign then the parties and the candidates have spent anywhere around BDT 5 billion. Additionally, the EC budgeted around BDT 7 billion to conduct the election – much of which reached the grassroots.

This sudden burst of income at the lowest tier of the economy generally shows a positive impact on the economy. Hence, Bangladesh should be able to sustain the overall growth trend in the mid-term, if not in the short-run.

Public investment and sustained gains in private consumption should remain as the key driver for the economy. However, to manage the budget deficit, the new government can consider tax reform to increase tax revenue post¬election. A new value-added tax (VAT) law is due to come into effect in fiscal year 2019/20 (July-June).

Trade war and

trade flows to push production to more expensive locations, forcing up prices and reducing efficiency. This will create economies are likely to experience collateral damage.

Tariffs generally do not reduce trade but shift it to new destinations. After the new tariff, importers in China and the US will look for alternative suppliers. This can open new opportunities for exporters in third-party markets like Bangladesh.

Probably the most conceivable channel of harnessing the benefit for Bangladesh is the RMG sector. Bangladesh is the second-largest exporter of RMGs in the world after China. Even before the trade war, Bangladesh’s share in global RMG exports had been growing, owing to its low-cost production credentials. Major international fashion brands such as H&M, GAP, Levi’s and Zara already have manufacturing facilities in Bangladesh. That is, if tariffs on imports from China go up then these brands can easily divert orders to Bangladesh. The good thing is that Bangladesh seems to have the access capacity to absorb the immediate increase in orders. In fact, already Bangladesh seems to have started benefitting from this. There is a report of several export orders switching from China to Bangladesh and also several buyers have initiated purchases from Bangladesh for the first time.

There are, however, two risks for this advantage to continue. Countries like Vietnam and India can actually bag a higher portion of market share that is left out by China. More specifically, only India has the ability to match the scale of China (see Fig 13) and the country also produces cotton. India also has the necessary access to capital to invest on a large scale. Hence, they have a competitive edge over Bangladesh. Secondly, it is expected that Chinese manufacturers will refocus their attention on the European market. This will make the market more competitive for all current exports including Bangladesh’s, eventually reducing Bangladesh’s share in that market.

Inflation to be moderate

According to data released by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), point to point consumer prices rose by 5.35 per cent in December compared with an average increase of 5.58 per cent in the first 10 months of the year (see Fig 14). Food price inflation has continued to ease as agriculture production in the country recovers following devastating floods in 2017. Food prices rose at an average rate of 5.1 per cent year on year in October, the lowest rate since August 2016.

The BBS data showed that the point to point non-food inflation rate, however, declined slightly to 5.49 per cent in November down from 5.90 per cent in October.

Remittance showing an uncertain trend

Remittances in 2018 were the highest that the country has ever recorded – albeit slightly weaker than our expectations, owing to cooling in oil prices in the latter months of the year. The main reason for the strength in inflows was a recovery in global oil prices last year.

According to data published by Bangladesh Bank, the inflow of workers’ remittances decreased at the start of FY19 and subsequently settled during the last four months of the year (see Fig 15). The latest report by the World Bank suggests that officially-recorded remittances to developing countries will increase by 10.8 per cent and South Asian Countries by 13.5 per cent in 2018. This new record level follows a robust growth of 7.8 per cent in 2017. The report identifies Bangladesh as a gainer and is in the third position in South Asia with USD 15.9 billion inward remittances with India (USD 79.5 billion) and Pakistan (USD 20.9 billion) is considerably ahead of Bangladesh.

It is expected that in the next six months, remittance flow will slightly increase supported by a weaker taka against the US dollar. Furthermore, the government’s clampdown on illegal remittance channels will also continue to support remittance earnings from official channels in 2019.

However, the pace of migrant worker deployments from Bangladesh for the first three quarters of 2018 has slowed by 25 per cent (0.55 million, compared with 0.73 million in the same period of 2017). The adoption of fiscal consolidation measures and stricter immigration rules in the Gulf region may also impede growth in remittance inflows to Bangladesh.

Some of the political developments in the Middle East can drive down oil prices further in 2019. Such a change is a double-edged sword for Bangladesh. Lower oil prices mean savings in foreign currency for Bangladesh – a country that is almost totally dependent on imported primary energy. At the same time, remittances to Bangladesh are highly correlated with oil prices, as the wages of migrant Bangladeshi workers in Middle East vary with movements in oil prices.

Brexit and Bangladesh

The UK is an important trading and development partner for Bangladesh. According to Bangladesh Bank data, it is the third largest export destination for Bangladeshi apparels encompassing more than USD 4 billion worth of shipments a year. The UK is also a tested partner of Bangladesh’s development. Bangladesh enjoys the second position in terms of development assistance from UK’s side. Additionally, more than 2,000 UK firms are currently operating in Bangladesh.

Brexit may have a negative impact on the UK’s economy. Uncertainties associated with the process, as experts are predicting, can cause immediate-term negative economic impacts.

One of the more likely immediate term impacts is weakening pound sterling— which is going to affect Bangladeshi exports to the UK market and remittances from the UK. Development assistance from the UK will also be unfavourably affected. Finally, given the close ties that Bangladesh enjoys with the UK, any negative impact on UK’s economy is sure to have a corresponding impact felt by Bangladeshis living in the country and at the UK.

However, on a positive note, Brexit may open half of the import market of UK for renegotiation which countries like Bangladesh can grab with the right offering. Similarly, a good chunk of EU market will be open for discussion as well.

Global outlook

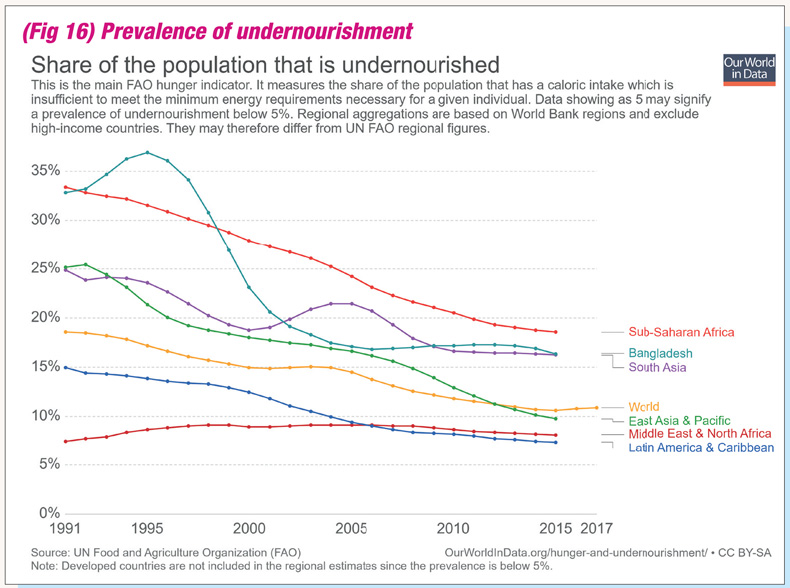

Ending hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition of all forms is at the core of Goal 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals agenda (see Fig 16). However, with new pieces of evidence indicating a rise in the global hunger situation, the question remains whether all countries will be able to make adequate progress towards achieving this ambitious goal by 2030. The Global Hunger Index 201825 report estimates that at the current rate of progress, an estimated 50 countries will fall short of the target of achieving zero hunger within 2030.

The latest State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World26 report reveals that the number of undernourished people reached a staggering 821 million in 2017, implying that one out of every nine people in the world remains affected by undernourishment. In addition to conflict and violence in many regions, adverse impacts of climate change have been identified as a key driver to worsen food security. The situation is most persistent in South Asia and sub-Saharan African nations where people are already living in vulnerability and disadvantage. Globally, the South Asian region has the highest rates of stunting and wasting.

State of Bangladesh

One of the success stories of MDGs, Bangladesh made remarkable progress in several social indicators including reducing poverty, ensuring food security, lowering maternal mortality ratio and infant and under-five mortality rates, primary school enrolment and gender parity in primary and secondary education. Despite the progress made during the MDG period, the prevailing high levels of malnutrition and undernutrition pose significant challenges for the country. Although the prevalence of undernourishment decreased slightly from 17.2 per cent in 2010 to 16.4 per cent in 2016, greater effort is needed to reduce the rate to 10 per cent within 2030.

The rise in the prevalence of stunting (height for age) among children under 5 years of age from 15.3 per cent in 2011 to 36.1 per cent in 2014 is most concerning. Malnutrition in early stages of life has a long-lasting impact on economic growth, human capital development, and labour productivity. The proportion of wasted children (weight for height) declined from 15.6 per cent in 2011 to 14.3 per cent in 2014, while that of overweight children (weight for height) also declined from 1.9 per cent to 1.6 per cent during the same period.

Fora country that is hoping to make the best use of the demographic dividend to break free from the cycle of underdevelopment, this is indeed bad news.

It is clear that to transform the youth population into a healthy workforce, addressing the challenges of hunger, undernourishment and malnutrition is a pre-condition. The National Micronutrients Status Survey 2011-12 report estimates that micronutrients deficiency is accounted for the loss of USD 7.9 billion in the national GDP. Naturally, the loss is simply cumulative – the malnourished children of today will fail to deliver the growth as a young citizen too.

Key challenges

Sustainable food production and climate change

Bangladesh is among the most precarious and unpredictable countries due to climate risks . Agricultural production is anticipated to be extensively harmed by the rapid expanse of soil salinity that arose from sea levels rising, tidal flooding, and intensifying storm gushes. It is estimated that 30 per cent of Bangladesh’s cultivable land is located in coastal areas. The increase in soil salinity will lead to a 15.6 per cent wane in the harvest of high-yield rice. Other agriculture-related challenges are a loss of arable land due to rapid urbanisation. On the whole, though, Bangladesh has done well to increase agricultural productivity to keep the net average production growth at around 3.8 per cent over the last decade. Additionally, salinity, as well as excessive use of groundwater, are already impacting irrigation during the dry season. Given the declining groundwater tables and water quality issues in Bangladesh, it will be extremely difficult to exploit groundwater resources sustainably. Without an increase in water productivity, it will be difficult to meet even reduced demand.

The gradual increase of C02 level in rural Bangladesh where most of the rice is produced can have a significant impact on the nutrition of a community who are almost exclusively dependent on rice.

The productivity of agricultural labour and other challenges

Generally speaking, the labour productivity of Bangladesh is not among the highest. Low level of skill, a low adaptation of technology and lower productivity of the land are all contributing factors. A 2014 BRAC study found that roughly 40 per cent of the cultivated land continues to be single cropped. Quite expectedly, it is the large and medium farms who have more single cropped land than small farms. To make the situation worse, our agricultural productivity is low. For example, the current yield gap (the gap between potential production and actual production) actually means as much as 36.7 million tonnes of potential loss in rice by 2021.

Fisheries and livestock challenges

In terms of food utilisation, the benefits of fish in the human diet are well established. Especially in Bangladesh, fish represents a major source of dietary protein for much of rural communities. The recent FAO report ranked Bangladesh as the fifth largest producer of inland fish after China, India, Indonesia and Vietnam. The global report also mentioned how the sector is fast becoming a key driver for alleviating poverty by creating huge employment and developing the supply chain.

However, habitat destruction due to water pollution, urbanisation, and salinity intrusion are all critical risk factors for sustainable growth of the sector and hence, for public health and nutrition. Overfishing, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices of both inland and coastal also pose a sustainability issue.

Investment in health and nutrition

Another major challenge for Bangladesh in achieving SDG 2 is the low government expenditure on health. Public health expenditure in Bangladesh is only 0.8 per cent of GDP. This is one of the lowest in South Asia. Improvement in nutrition and health will require a significant increase in public health expenditure.

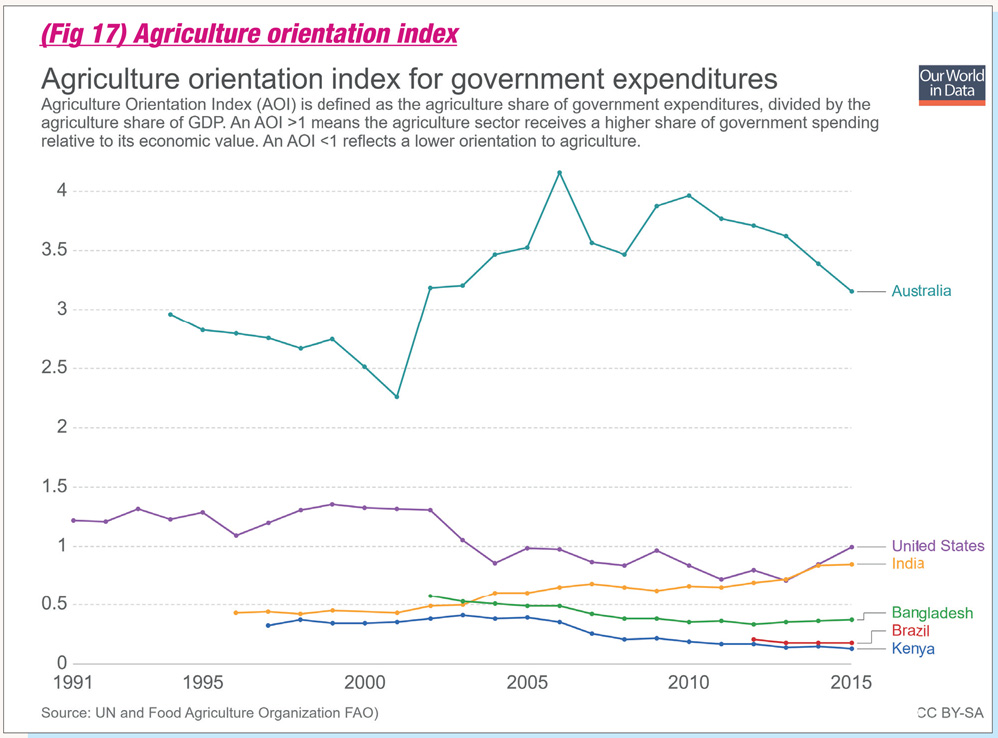

One of the limiting factors in this regard is what the SDG terms as Agricultural Orientation of public expenditure (indicator 2.A.1). Apparently, the share of budget allocation to the agricultural sector compared to the sector’s contribution to the GDP is only 37 per cent, whereas developed countries such as the USA and Australia spend much more in comparison (see Fig 17). Notably, the Bangladesh Second Country Investment Plan (CIP2) prepared by Food Planning and Monitoring Unit (FPMU) under Ministry of Food proposed 13 investment programmes to improve food and nutrition security in the country, at an estimated total cost of USD 9.2 billion—which is way more than what the current expenditure package offers.

Poverty and behavioural issues

A third of Bangladeshi pre-school children and half of the pregnant women are anaemic. Vitamin A deficiency affects every child in live, and vitamin B12 deficiency one child in three. Lack of awareness and inappropriate food choices are two of the key challenges in this regard. Additionally, early marriage and teenage pregnancies leading to a high prevalence of low birth weight (22 per cent) are among the key determinants of malnutrition. Similarly, only half of the children are exclusively breasted and complementary feeding practices are inadequate to meet the nutritional requirements of infants and young children.

A multi-sectoral approach is key

To overcome these challenges, a coordinated multi-sectoral approach is needed at national to local levels. The National Nutrition Policy 2015 focused on ensuring the availability of adequate and safe food as well as diversification of diets through both nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific interventions.The Global Hunger Index 2018 reiterated this policy priority by underscoring the importance of promoting nutrition-sensitive interventions in agriculture, including the production of nutrient-rich crops and fish for improved nutrition. Strong political consensus and local government actions are required to attain such coordination.

Greater policy support is needed for small-scale farmers and low-paid food producers to build their resilience against the adverse impacts of climate change. Public investment in developing appropriate crop variety and intensive extension work will be critical.

BRAC’S focus

Non-governmental organisations like BRAC have an important role to play for successful implementation of SDG 2. BRAG, with its extensive operation throughout the country, has unparalleled access at the grassroots to provide service in remote areas as well as to help people combat climate change. Through the Health, Nutrition and Population Programme (HNPP) and Agriculture and Food Security Programme (AFSP), BRAC is contributing to improve dietary practices of the target population, as well as to achieve food security and improved nutritional status of two million marginalised people. In addition, Ultra-Poor Graduation (UPG) programme provides support to households to enhance food and nutrition security with resilient livelihoods and enterprises, the targeting to impact 400,000 households by 2020. Furthermore, BRAC Seed and Agro Enterprise, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), BRAC Dairy and Food Project, and the Integrated Development Programme (IDP) contribute to SDG 2 both directly and indirectly. Effective collaboration of government with NGOs in the areas of health, nutrition, and food security can produce a synergic effect to achieve SDG 2.

KAM Morshed Is the director of Advocacy for Social Change, Technology and Partnership Strengthening, BRAC.