Self-identity, aspirations and expectations of Bangladeshi youth

Our cities, our solutions

March 14, 2019

Am I okay?

March 19, 2019Self-identity, aspirations and expectations of Bangladeshi youth

Bangladesh has been experiencing a demographic dividend for the last 10 years. We have gotten used to more people being of working age than non-working age. This is not expected to end any time soon. The current economic growth predictions forecast that this dividend will continue until 2040.

Currently, more than 65 per cent of the country’s population are of working age. Everyone in the development sector is talking about the youth. However, much of this discussion is often limited to specific segments of the youth.

To provide a comprehensive picture, BRAC conducted a nationwide survey on a total of 4,200 young people (between the ages of 15-35). An equal ratio of men and women were interviewed – across 150 sub-districts and 51 districts of Bangladesh. The survey covered a range of topics relevant to the youth.

In this piece, we only focus on the expectations and aspirations of the youth – with respect to their personal lives and how they feel as citizens of this country. This theme is relevant to politics, research, policy and intervention design. A full report of the survey will be published later in 2019.

Self-identity: How do the youth prefer to identify themselves?

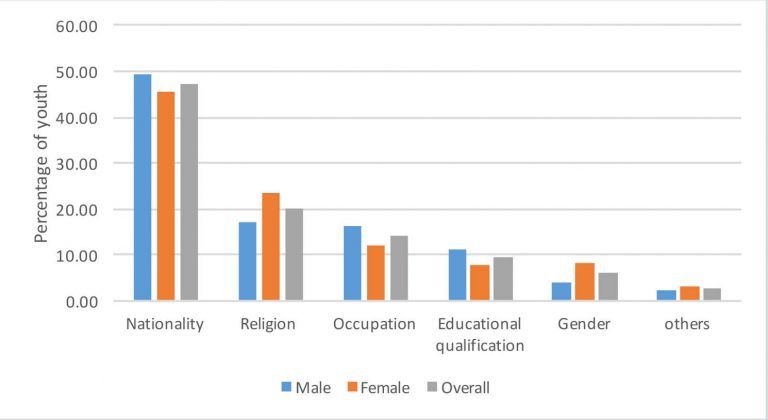

The term ‘self-identity’ reflects how people see themselves – what kind of labels they prefer to describe themselves. During the survey, we asked participants how they preferred to identify themselves – giving them five pre-set options and one open one.

Across the different groups and categories, ‘nationality’ was the top answer, followed by ‘religion’. This is not unexpected as these two factors and the struggles between them have remained to be the critical factors behind the birth of our nation, politics and identity.

While for both young men and women, the top two factors were ‘nationality’ and ‘religion’, the proportion of women preferring to identify themselves in terms of their religion was much higher compared to men.

Self-identity and gender

‘How consistent is this relative gender gap between young men’s and women’s preference of religion as the main self-identifier?’ This was further explored by disaggregating gender across several variables – such as regional, rural-urban and socioeconomic status.

An interesting pattern was found when the socioeconomic status filter was used. Young women from the poorest households preferred religion as the most preferred marker of their self-identity compared to young men from the same socioeconomic status. When it came to young people from rich households, young men preferred to identify themselves in terms of religion more than women.

Mind the gap: How does the gender gap of religion as self-identity change with economic status?

Young people with SSC and higher levels of education opted for ‘religion’ less compared to those who had no formal education. In contrast, the number of young people who chose ‘nationality’ as part of their self-identity was significantly higher and it remained relatively unchanged across different levels of educational.

Self-identity and level of education

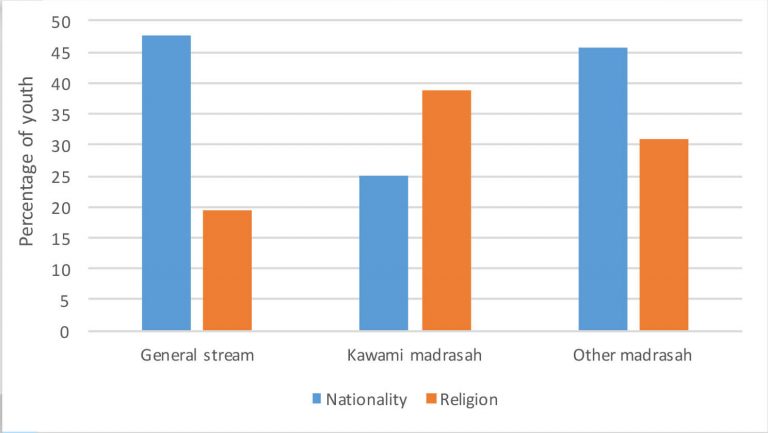

The answers also varied depending on the type of educational institutes the youth belonged to. A high number of people with Qawmi madrasah background preferred ‘religion’ over ‘nationality’ compared to those belonging to the general stream of education and other madrasahs.

Self-identity and type of educational institution

Age also seemed to play an important role in defining one’s self-identity. ‘Nationality’ as an integral part of self-identity remained predominant across the different age groups. The gap between ‘nationality’ and ‘religion’ narrowed post 25 years and beyond.

Self-identity and age

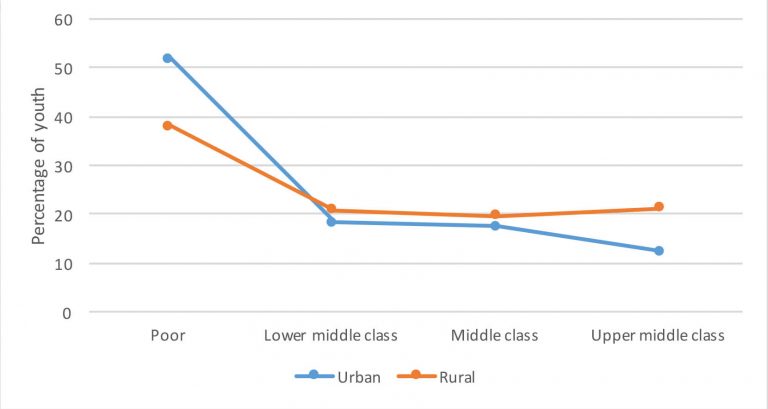

We also explored if ‘religion’ as part of self-identity had any relevance with the participant’s socioeconomic and rural-urban statuses. Given the growth in rural income and the rise of a rural middle-class, this was an important pattern to examine. An expected general pattern was observed – young people with improved economic status preferred ‘religion’ less, as indicated in the graph below.

However, there is a rural-urban divide here – young people who came from a rural middle-class background, especially the upper middle-class, reported a much higher preference for ‘religion’ compared to their urban counterparts. The young urban poor, on the other hand, has a stronger preference for ‘religion’ compared to their rural counterparts.

Religion as self-identity: Socioeconomic status and rural-urban pattern

Freedom of choice: Persistent gender gap

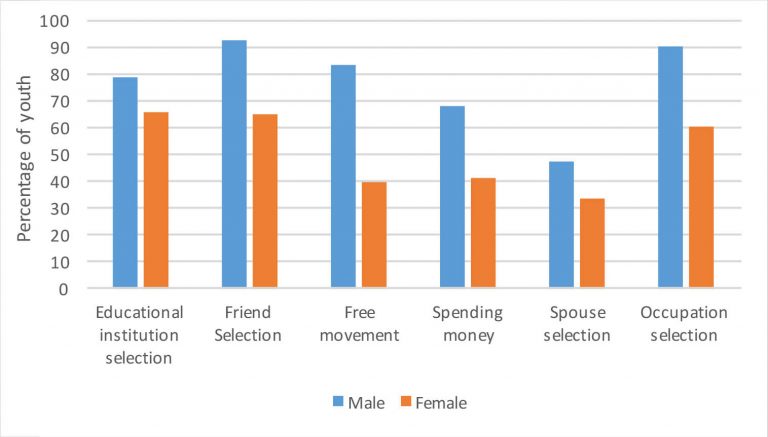

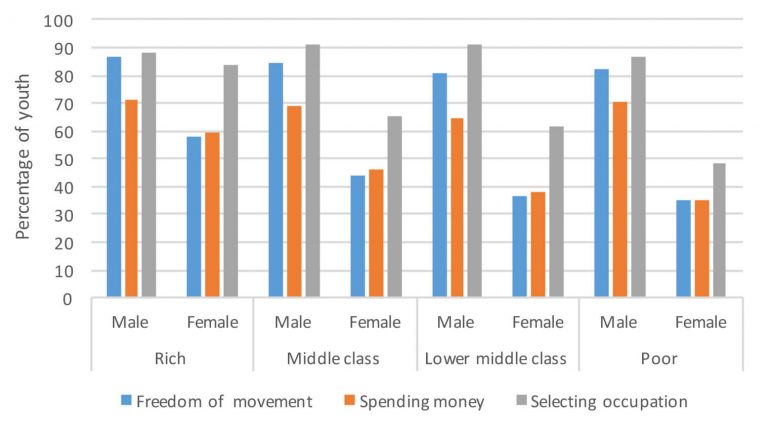

Establishing at least some degree of independence is a major area of concern for young people, as in most cases they must continuously engage or negotiate with their parents/guardians to ascertain their ‘freedom of choice’ in different spheres of their lives. During the survey, the youth were asked about the extent of freedom they enjoy in certain activities, such as choosing friends/ spouse/educational institutions/occupation, spending money, and physical mobility.

Overall, the ‘freedom of choice’ appears to be quite high, except in the cases of ‘spending money’ and ‘spouse selection’.

But when the gender disaggregated results were looked at, a massive gap was found between the experiences of young men and women across all the different aspects considered here. The gender gap in terms of ‘freedom of choice’ was also seen and this remains to be largely invariant to economic status, suggesting that this is a persistent challenge.

Freedom of choice and gender

Freedom of choice and gender: Persistence across economic status

Youth aspirations: Focus on education and intergenerational investments

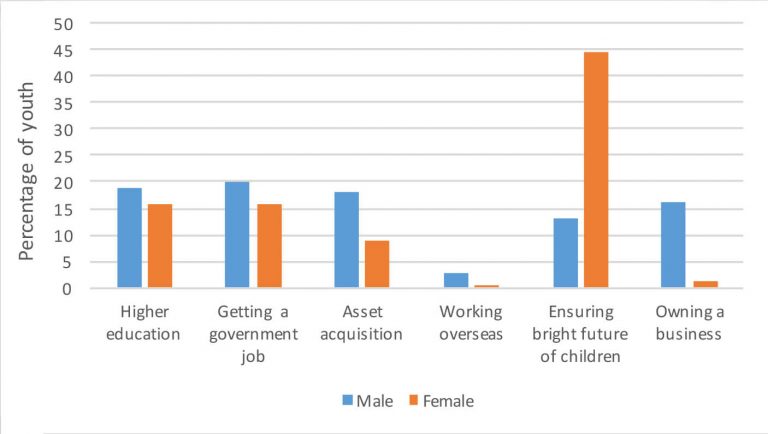

During the survey, the researchers tried to get some idea about the person’s goals in life. In particular, they were asked, “Among the different things that you want to achieve in life, what is the single most important one?”

As this was an open-ended question, the range of their responses was quite varied. However, there were a few particular ones that turned out to be the most prominent or common.

From the gender disaggregated results, it was seen that while ‘ensuring a bright future for their children’ is the most common goal among the young women, for men it is ‘getting a government job’, followed closely by higher education, asset acquisition and owning a business. All of these are important to women as well, but to a much lesser degree.

Life goals on the basis of gender

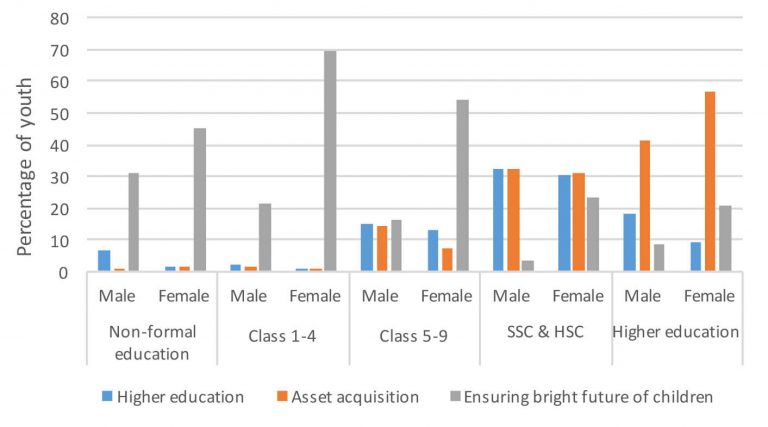

Disaggregating the youth’s most important life goals further – on the basis of gender and education – it was seen that ‘education’ is a big driver of the responses for young women who received higher education (‘ensuring bright future for children’ as the predominant life goal is replaced by life goals of ‘higher education’ and ‘asset acquisition’).

Life goals on the basis of gender and educational level

From results disaggregated by self-perceived socioeconomic status of the households, substantial difference was noticed among the priorities of youth coming from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

For example, ‘ensuring a bright future for their children’ is the priority for majority of the youth coming from ultra-poor households, followed by ‘asset acquisition’. On the other hand, for those coming from rich households, obtaining ‘higher education’, ‘getting a government job’ and ‘owning a business’ are among the most common goals. If the overall picture is considered, these responses make sense. Those who are ultra-poor, are often unable to make much changes in their own lives due to lack of scope and time. For them, the only sustainable pathway out of poverty is to ensure a better future for their next generation, which is why they try to invest in their children’s future as much as possible. In doing so, they particularly invest in their children’s education (ie, human capital development) and in establishing a solid asset base.

On the contrary, those coming from rich socioeconomic backgrounds do not need to worry about ‘acquiring assets’ and ‘a bright future for their children’ (as their high socioeconomic status often ensures their children’s access to quality education and high-quality services). This is why, they are able to focus on ways of ensuring that they maintain their high socioeconomic status (indirectly by improving human capital and directly by obtaining high-quality jobs and investing in their own business).

Overall, about 9 per cent of the youth interviewed reported ‘not thinking about their future’ and this shows an interesting inverse U pattern with the youth from the richest and the poorest background (reporting the lowest on this).

Life goals and socioeconomic status

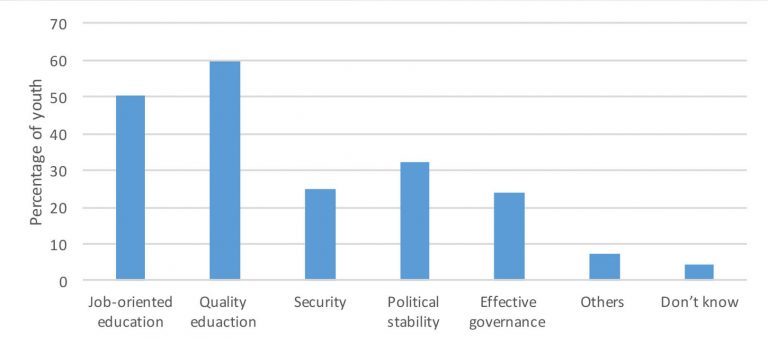

Expectation about the country: Drivers and constraints

Given that the youth are a substantial portion of the total population of Bangladesh and the country’s future direction will depend a lot on them, it is important to know what their thoughts and expectations are about the country’s future. In order to get a sense of this, several relevant questions were asked. In responding to “Which factors do you consider to be the most important for the country’s socioeconomic development?”, the majority identified two key themes – one related to education in terms of more job-oriented and improved quality of education, while the other set of factors related to security, political stability, effective governance, etc.

Key drivers of development

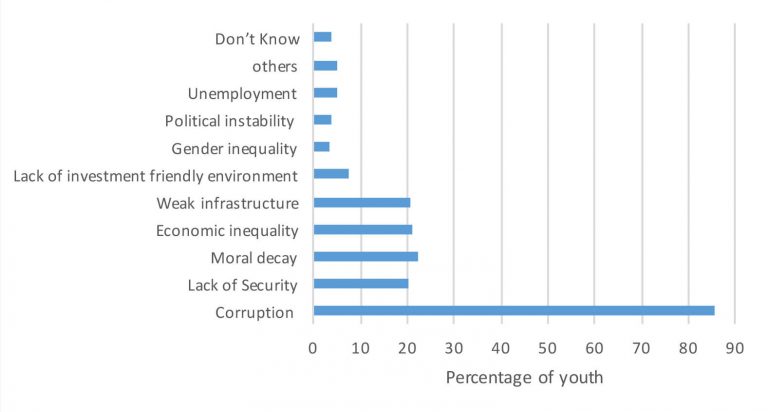

The participants were also asked what they considered to be major obstacles in achieving socioeconomic development of the country. The most frequent response, by far, was ‘corruption’, followed by related issues of poor governance such as ‘lack of security’ and ‘moral decay’.

Key constraints to development

Moving forward

A number of interesting patterns as to how the youth self-identified themselves were found. In the overall picture, young people predominantly preferred ‘nationality’ followed by ‘religion’ as integral parts of themselves. This calls for further analysis and research. The role of ‘religion’ and ‘nationality’ in forming one’s self-identity and how these interact to form opinions, shape perspectives and politics of the youth are vital when it comes to understanding the future of the society and its polity. The gender and rural-urban divide, especially among the youth from the middle socioeconomic class is of particular importance for deeper understanding.Young women are at a disadvantage with respect to all major domains of ‘freedom of choice’, and this disadvantage is persistent across all economic statuses. These ‘unfreedoms’ are both intrinsically and instrumentally important, as they are adversely affecting their life goals and human potential. A better understanding of the relationship between such perceived ‘unfreedoms’ (with the relative importance of ‘religion’) and self-identity found among young women is required.

Aspirations measured in terms of life goals by the youth in the aggregate is also highly gendered. Young men expressed relatively stronger aspirations of entrepreneurship such as ‘owning a business’, or ‘asset acquisition’ compared to young women.

Relatively lower level of gender gap were found in terms of life goals in areas that are related to ‘education’ or ‘employment’. Interestingly, few participants chose the option of ‘migrating overseas’ as their main life goal. Young women, who were less educated or whose educational level was below SSC, preferred the option of ‘ensuring a bright future for their children’ as their most important life goal. This indicates that there is a critical need for policies and interventions design to ensure the continuation of female education beyond SSC.

We also found a rich-poor divide in terms of life goals – youth from poorer households tend to prioritise ‘ensuring a bright future for their children’ as a life goal as opposed to those who belonged to higher levels of economic status. This only indicates that more interventions are needed in pursuit of making youth from poorer backgrounds more financially sound. The youth think quality general education is the most important driver for the overall development of the country, followed by good governance which includes security and political stability, and tackling corruption.

-Md Shakil Ahmed is a research associate and Anindita Bhattacharjee is a senior research associate at BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD), BRAC University.